There has been quite a lot of Coronavirus controversy about face masks of various types and who should wear them. There are studies on how much protection a wearer is given from different mask styles, standards and materials, there are studies on what happens to an infected person who wears a mask. There are lots of very strident and certain opinions offered on whether people absolutely should or absolutely shouldn’t be wearing masks. There are not a lot of people with answers to some specific questions I had, so I set out to answer at least one of them.

A mask is a filter of stuff, it isn’t a solid barrier, it will let some stuff through. It works a bit like the way sunglasses filter light. A face mask filters small particles instead of light but the principle is similar. Your sunglasses might have a tint that filters out 70% (typical of category 2 glasses) of the light – letting 30% through to your eyes. If you were to double up the glasses the first pair would let through 30% and the second pair would let through 30% of what got past the first set – so 30% of 30% which is 9% will be let through. The two 70% sunglass filters when used together block 91% of the incoming light – and this works exactly as expected for normal tinted lenses.

If you were to do this experiment with two polarised sunglass lenses instead of plain tinted glasses you will find that your neat maths and logical expectations go very wrong. These don’t randomly filter a percentage of the inbound light, they allow through a non-random polarisation of light. the second glass will either allow through pretty much everything the first one allowed through, or it will block pretty much all of it depending on orientation. I don’t want to go too much into the detail of light polarisation, the point here is that filters can sometimes surprise and not add up in the way you might expect. How do face masks add up? Are they surprising or not?

This is a question that doesn’t appear to have been studied in detail, so I thought I would do a bit of backyard science to find out roughly what we might expect to happen. This is Mythbusters grade science, I have no doubt that people in lab coats with a string of letters after their name will be holding their heads in their hands at the sight of this, but I am still going to get to the same qualitative answer as would be found in more controlled conditions. The setup here is on a pool table in a garage. As it is in a garage it is easy to open the roller door and replace all the air in the room to reset. I have two cardboard packing boxes, Alice and Bob representing a couple of people in a supermarket discussing which one of them should take the last packet of bog roll. Alice is infectious but doesn’t know it as she is asymptomatic. That box contains a smoke machine. Bob is susceptible and contains a particle counter. Each has a mouth cut out facing each other. I can move them back and forward, cover one or both mouths with different materials, and maybe apply positive or negative pressure at various points. I can also give Alice a tap to simulate a cough. The video below shows testing the setup prior to making any measurements.

From just that we can see some interesting things, a cough can form a smoke ring – which may mean that the droplets from a sudden dry cough could travel considerably further than you might expect if they form a stable vortex rather than falling after a certain distance. I don’t know if that is true for real human coughs and I am not going to inhale enough smoke to test it. Regular smokers probably already know how far a cough can travel and whether a smoke ring can be inadvertently formed. It is also possible that if someone coughs at you, your best strategy might be to cough right back at them to prevent theirs from landing! I am not sure this is terribly good advice and an arms race of coughs is probably as sensible as any other escalating arms race.

I tried a few different mask materials and settled on a loosely knitted blanket (the thing I pick up in the video). This is a terrible material as a mask, which means it is ideal for finding out how terrible masks perform. The better mask materials meant more smoke escaped from other places and just wasn’t going to be very informative. The first thing to note is that this terrible mask completely stopped the long range coughs – it let the particles through but they just hung around in a cloud close to Alice. There is no way to form a vortex ring with any mask in place.

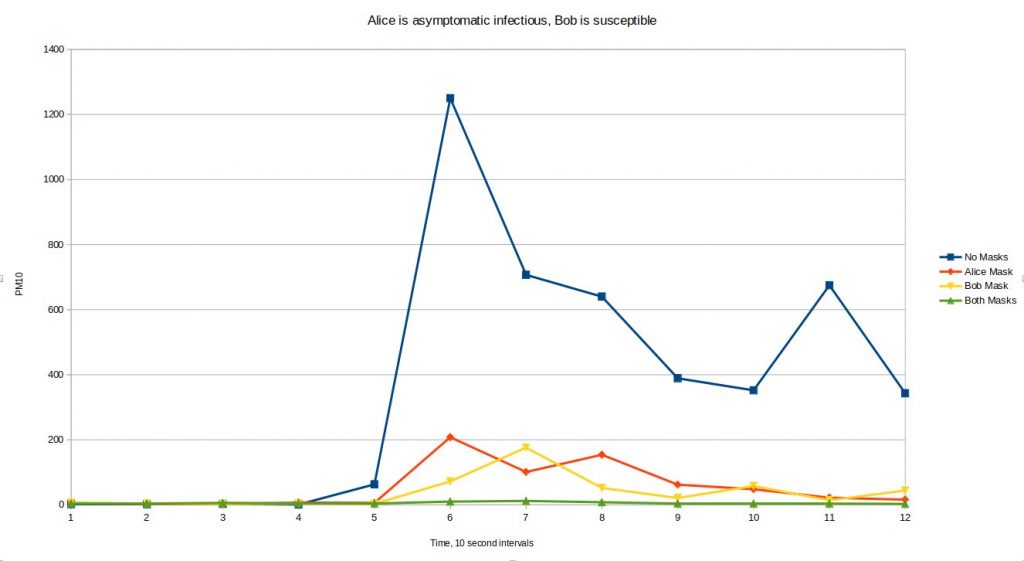

I tested the situation of no masks, a mask for Alice, a mask for Bob and both wearing masks. The graph below is what the particle counter in Bob recorded at 10 second intervals. The start time doesn’t mean much – don’t read anything into which one showed an effect the soonest, but it was roughly 30 seconds generating smoke before it got to Bob. You are really looking at the area under the curve as the amount of smoke seen.

This was just one run of each scenario, followed by refreshing the air to get back down to the single digit background level before trying the next. I will repeat it a bunch of times and see how consistent it is, but on that first run we can see that the single mask is roughly as effective whoever is wearing it (which surprised me a bit, I thought the mask on Alice would be more effective) and two masks is very effective, consistent with masks behaving like unsurprising filters.

I did several more runs it seems that for a 2 minute period the mask blocks around 85% of particles, regardless of who is wearing it. If both wear the mask it blocks around 97%, which is about what would be expected if they are random filters. More testing will be done when the weather conditions are favorable. I would stress that those numbers are not comparable with percentages you will see others quoting for testing different mask materials.

FAQs

- But those are not real masks!

Indeed they are not. The mask is intentionally very rubbish as the question is about the addition of two poor quality masks. I used the most porous material I had to hand so that the effect was most testable. Using something like a surgical mask stops the long range cough and it leaks out of the sides. Using an N95 painting mask stops pretty much everything and the smoke leaks out from other parts of the box. Other people have studied different masks, go read their data. All I will say is that a tshirt or cotton sheet was too good to usefully test for the effect I was looking for on the apparatus I put together.

- Smoke isn’t droplets!

No, but it isn’t far out, and it isn’t really smoke. The smoke machine turns a water and glycerol based fluid into a cloud of droplets that are in the same ballpark as the size of the exhaled droplets that masks are tested against. They are also perfect for the particle counter.

- This should be done in a lab, not a dusty garage!

Yes. Let me know if your results agree with mine when you are done in the lab. My ambient air is very low in particulates, probably cleaner than most city labs.

- But the WHO/My local health authority/Someone on the internet insists the public absolutely shouldn’t wear masks!

Great, follow their advice. None of this is advice on what to do, I am just trying to establish whether two masks add up in an expected or unexpected way, which is a question that seemed both reasonable and unanswered.

- Bob can get infected from his mask when removing his mask incorrectly!

Maybe so. I don’t attempt to answer that with this experiment, however any particles contaminating Bob’s mask would appear to be particles he would otherwise have inhaled – they are just getting a second chance. The mask doesn’t seem to be something you would expect to be more contaminated than any other article of clothing Bob would be wearing – so if you are treating the mask as a biohazard you should probably treat the rest of his outer clothes the same way.

- Should I buy a mask?

Definitely don’t buy a type of mask that could be better used by a healthcare worker. Don’t compete with medical staff for access to that supply chain. This has nothing to do with the experiment, and I am not advising you to do anything in particular, but I am advising you not to take masks that healthcare workers could use.

- What type of DIY mask should I make?

I have no advice for you on this, all I am trying to do is give a little objective information on how much joint effectiveness you can reasonably expect from two people wearing masks compared to one of them wearing a mask.

- Why on earth do you have a particle counter?

It is for measuring air quality. It isn’t an expensive thing, the component cost around €20 you can get one packaged in a handheld reader for less than €100. I wanted to do my own electronics, so I have a microcontroller reading it and reporting the results over MQTT to my laptop. It is a Plantower PMS7003. I have the smoke machine because everyone needs a smoke machine sometimes.

- Do you wear a mask?

I live in the middle of nowhere and I am a champion social distancer. I have a shemagh which is mostly to reduce the number of flies I eat when cycling, but now I keep it over my mouth when going in the shop.

- How good do two masks have to be to be the approximate equivalent of a single N95 mask?

The N95 mask has to filter a minimum of 95% of airborne particles. To get to that level with two masks assuming they add up like normal filters the calculation is (1-sqrt(1-0.95)) which works out to about 78% if they are two equal masks. A real N95 mask properly fitted probably performs better than 95%, and two bad masks are not a replacement for one good one in a healthcare setting. This is just a back of the envelope calculation that seems to show a pair of reasonable DIY masks could have a similar joint effectiveness as a standardised mask.

- Are their other benefits or drawbacks of wearing masks?

Yes, in particular they may either help to remind you not to touch your face, or they may cause you to adjust them a lot and touch your face more in the process. I have no idea which one happens the most, probably depends on the person. Not really my type of experiment I am afraid.